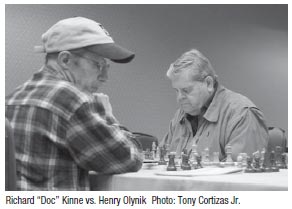

The second round of the Boston Continental Amateur was a game of a lifetime for me. I lost. Why was the game so memorable? The second round of the Boston Continental Amateur was a game of a lifetime for me. I lost. Why was the game so memorable?

My opponent, Henry Olynik of White Plains, NY was blind. And only in chess could you hope to play an equal game against a United States Champion! There are specifi c rules for blind chess players which I’d known about from the rulebook as a Certified USCF Tournament Director since the early 80s. Blind chess players use a special board. The white squares are recessed 2 mm. All of the pieces are secured into the board via pegs. The Black pieces have tiny metal balls, or even sometimes dull pins, on their tops so that the blind player can tell the difference between the colors. Touch move is done differently. A player’s hands roam all over the board and pieces as the player “sees” the board. Only when a piece is taken out of its peg is it deemed touched.

Procedures are different as well. The sighted player plays right next to the blind player on their own set, and both sets are kept in sync. Moves are called out by both players and confi rmed by both players. As White, Henry’s fi rst move started out when he said, “White Pawn on e2 to e4.”

“White Pawn on e2 to e4,” I confi rmed. My response: “Black Pawn on e7 to e5.”

“Got it,” Henry said. “Black Pawn on e7 to e5.” In the beginning this was quite distracting, but I got into a groove after a bit.

Not only was the game - playing with a blind player for the very fi rst time - fascinating, but Henry himself was fascinating. 70+ years old, he was born in the Ukraine and was caught up in Stalin’s Ukrainian killings where his father was taken and vanished just before Henry was born. At the age of fi ve he grew up in various concentration camps during WWII, and finally made it to the United States. He worked as an engineer in the 60s and was on the design team that created the LEM landing pads for Project Apollo.

In his early 40s he developed a brain tumor that had to be operated on. They opened up his head, sliced open a fl ap of his brain to get to the tumor, cut the olfactory nerves (Henry can no longer smell) to lift the non-malignant tumor out of the brain. Put back together again, Henry lost vision in one eye almost immediately, and over the next 30 years lost vision in the other eye, becoming blind.

That’s what I knew during the tournament, right after we played our game. It was only when I got home that I found out how special the game, and Henry, really was.

Today in Katonah, NY the Henry Olynik Chess Club resides at the Montfort Academy where Henry teaches the school’s students how to play chess. These kids are taught by a United States Chess Champion. Henry holds the 1999 United States Blind Chess Champion title! To this day he continue to compete in this championship.

Yea. Truly a game of a lifetime, with a truly unique person. Not bad for a Saturday, eh? |