“Bam, sucka!”

Somewhere between a summer night and a summer dawn, in the witching hours of a Saturday when the city sleeps, the crescendo of the chess players by the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Dunster Street in Cambridge can be heard for some distance.

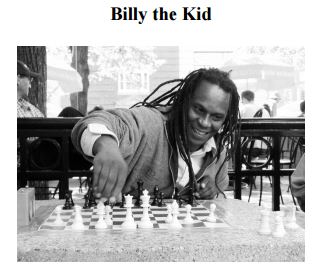

Of course, they don’t care. William Collins, the dreadlocked homeless man making the proclamation, is winning his game, and Billy Collins is not a quiet man. Perhaps the game is a crucial point in a match against a rival, or perhaps some New York or Philadelphia hustler passing through town is now regretting challenging the Harvard Square icon for small stakes. The thrill of blitz in the Square is the same. Of course, they don’t care. William Collins, the dreadlocked homeless man making the proclamation, is winning his game, and Billy Collins is not a quiet man. Perhaps the game is a crucial point in a match against a rival, or perhaps some New York or Philadelphia hustler passing through town is now regretting challenging the Harvard Square icon for small stakes. The thrill of blitz in the Square is the same.

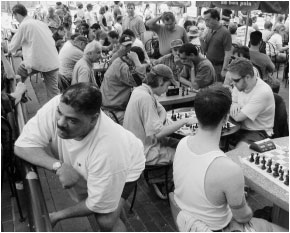

Some hours later, the area in front of the Au Bon Pain fills to its brim with all variety of visitors, tourists from around the world and locals who come by daily. But the chess tables – sturdy things of stone with checkered engravings of sixty-four squares on top – are reserved for their intended use, and they fill up, even spilling over into the plain black tables closer to the Holyoke Center.

When I began frequenting the Square around 2011, I heard murmurs that it was not as popular a site as it once was, but the place I saw was still bustling when weather permitted, headlined by strong regulars whose appetite for the game seemed insatiable. When I began frequenting the Square around 2011, I heard murmurs that it was not as popular a site as it once was, but the place I saw was still bustling when weather permitted, headlined by strong regulars whose appetite for the game seemed insatiable.

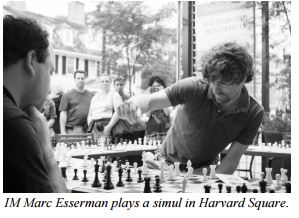

Marc Esserman was something of a big man on campus. Fresh off of earning his IM title, the Miami native who came to Harvard in 2001 for college had an incredible passion for the square, which was something of a second home to him. Considerably higher rated than anyone else visitors could reliably find, Esserman was also a fanatic of speed chess, with quick hands shaped by a childhood of competitive tennis and an innumerable body of experience with his favorite game. He would offer wild time odds, advertising forty seconds against five minutes to all comers and willing to go even lower – he claimed his record was twelve – against the right customer. A favorite variant featured an extra black queen on a7 for his opponent, an advantage which seemed insurmountable in theory. Marc, however, knew his way around such an obstacle, and bested even seasoned experts under the conditions, to his opponents’ great dismay.

Vadim Martirosov was a strong master who would occasionally hold private lessons in the Square. He played almost exclusively against a few select rivals, among them IM Esserman, his good friend NM Ilya Krasik, and of course Billy, with whom he would have long matches well into the night. Vadim Martirosov was a strong master who would occasionally hold private lessons in the Square. He played almost exclusively against a few select rivals, among them IM Esserman, his good friend NM Ilya Krasik, and of course Billy, with whom he would have long matches well into the night.

Vadim and Marc I had known previously through the community of tournament players, but there were many faces I would see around the Square and only around the Square, taking in countless games of blitz with no interest in more “serious” controls. This is not to say they were weak – every so-called amateur player was seasoned with years upon years of experience in the square, and they all had their tricks.

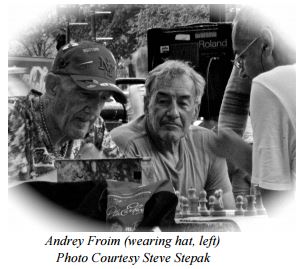

On weekdays, and particularly when school was in session and the area was more subdued, perhaps the person I saw most was an old Russian by the name of Andrey Froim. Insistent on using his huge Soviet analog clock, Andrey played all comers for two dollars a game. Never a tournament player in the United States, he was seen as master strength, and held his own even when some stronger players from afar would pay anonymous visits trying to hustle him. On weekdays, and particularly when school was in session and the area was more subdued, perhaps the person I saw most was an old Russian by the name of Andrey Froim. Insistent on using his huge Soviet analog clock, Andrey played all comers for two dollars a game. Never a tournament player in the United States, he was seen as master strength, and held his own even when some stronger players from afar would pay anonymous visits trying to hustle him.

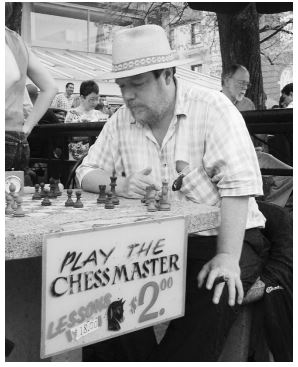

Another option for tourists looking to play for money was to visit the Chess Mister, a quiet curmudgeon who largely kept to himself. Of around 1600 strength and playing without a clock, he offered a vastly different pace and feel of play to the more intense players who surrounded him, though one which was more conducive at times to a casual tourist with limited knowledge of the game of chess.

There was talk of another player – a strong master who used to call the Square his own, who played more than anyone. His name was Murray Turnbull, and he was a legend in Harvard Square.

I had seen him when passing through the Square in my childhood, always offering two dollars a game, always with his iconic “Play the Chess Master” signage. But his activity had decreased, and though he still infrequently passed by, even those visits were dropping. Quietly, an era was ending.

Beginnings

The Harvard Square chess players of the 1970’s and early ‘80’s were a nomadic people, drifting from café to café in search of a hospitable arena. Murray was among them, as was chess photographer extraordinaire Steve Stepak and a few other regulars who would stick around in the coming decades. But it was a small group, and they were beholden to the whims of the café owners, who might on any given day deem them loiterers or noise pollutants and throw them back to searching for a place to play.

Louis Kane was something of a fan of chess, however, and he was also conveniently the founder of Au Bon Pain. By 1983, his five-year-old business was beginning to expand within the Boston area – he would spread to New York City the following year – and he wanted to make the Harvard Square location special.

Forbes Plaza, as it is formally called, was long ago just another city block in bustling Cambridge. That block was razed in the 1950’s, but the open space that came alongside the new Holyoke Center, a Harvard University building, was for decades overlooked and underused. Kane, seeing the area’s potential, installed tables and chairs in front of his new restaurant, including the row of stone structures that would become the headquarters of the Boston chess community.

William Collins came to Harvard Square in the 1970’s, but he didn't originally come for the chess. He was fond, he says of the hippie culture that had sprung up locally, and found comfort in the Bohemian crowd. William Collins came to Harvard Square in the 1970’s, but he didn't originally come for the chess. He was fond, he says of the hippie culture that had sprung up locally, and found comfort in the Bohemian crowd.

But Billy was also a chess player. A member of the school team at Braintree High, he remained active throughout his adult years and frequented local clubs. So when Murray Turnbull and Arnie DuBow started challenging comers in front of the new café, Billy jumped at the opportunity to test his mettle.

I sat down with Mr. Collins recently to discuss his experience with the Square, and he recalled this early experience as somewhat humbling. Often faced with weaker opponents growing up, his talent allowed him frequently to dominate, and that gave him a brash confidence he would find unwarranted against the two masters.

But confidence, Billy argues, was not the enemy. An avid boxing fan, he sees the winning spirit as a prerequisite to success, not its outcome.

“You can’t win a tournament if you come in thinking you’re going to lose. You have to come in knowing you can win,” Collins offered.

The experience with Murray and Arnie was a learning one, and Billy did not let his early missteps get him down. He kept coming as the Square blossomed, finding new opponents and new tools to use against them, amassing an arsenal of catchphrases which would become his iconic calling cards. What was once a brash, bombastic confidence has turned into a brasher bombastic confidence. Collins credited it as the key to an incredible day when he bested an onslaught of increasingly strong masters, among them perennial 2400 Chris Chase and IM Dave Vigorito, for a Boylston Club tournament sweep that would gain him close to a hundred rating points.

For helping the environment flourish where that confidence could grow, Collins credits Murray Turnbull first and foremost.

“He treated it like a job. Never missed a day. Murray was the only one who was there every single day. He would put in the hours. So even when he wasn’t getting games, he would still be sitting there waiting. I can’t do that, I could never sit for two or three hours, not playing. I’d be like, ‘damn, I could be out in the streets, begging – something.’ Just waiting, like that, I could never do. It was really important to him.”

Play the Chess Master

Before attempting to contact Murray Turnbull, I asked regulars in the Square if they happened to know his whereabouts offhand. They didn’t, and one suggested that we couldn’t be sure that the man was still alive. Before attempting to contact Murray Turnbull, I asked regulars in the Square if they happened to know his whereabouts offhand. They didn’t, and one suggested that we couldn’t be sure that the man was still alive.

“He is,” Chris Williams offered, “I’ve seen him on ICC. He has a handle there.”

The words were strangely prophetic.

Murray Turnbull lives only a few blocks from Harvard Square, in a condo by the corner of Concord Avenue and Garden Street. A diabetic, Turnbull – who also had a bout with oral cancer some years back – is in good shape now, and his space is simple and orderly.

For fun these days, Murray plays bullet chess on the Internet Chess Club. One minute a side, and he claims to have stockpiled close to 200,000 such games on the site, averaging by his estimate 70-80 per day. He has favorite systems – one cannot improvise in the opening in such a control, he asserts – for which he is quite enthusiastic. The Latvian Gambit (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 f5) is a favorite, as is the Albin Countergambit (1. d4 d5 2. c4 e5).

It turns out Billy’s assertion that Murray viewed his role as resident Chess Master as a job was no exaggeration. And now, Turnbull is, by his own words, retired.

He has fond memories of the Square – of the many famous players who came and faced him, his memories particularly fond of those he’d beaten. IM Kamran Shirazi, a longtime Massachusetts resident, apparently lost to Murray three games in a row, a run Turnbull attributes to his opening flexibility.

“[Shirazi] played some offbeat stuff, and would get people with it. There’s a thinking – ‘oh, I bet he won’t know what to do here,’ ‘I bet he’s never seen this move!’ – but the thing is that I played everyone. I’d seen every weird opening there was, and I’d learned not to be bothered by it.”

He was not as successful in beating Nigel Short when the British chess legend passed through town, though he laments that he should have drawn one of their games. He recalled in great detail the ending that he had: three pawns against Murray’s two, all on the same side, with a knight for Short against a bishop and a queen and a rook of each color. If he could only exchange down to one piece, Turnbull remarked, the game would be a draw. But alas, the then-U.K. champion flagged him.

This was all in the 1980’s and ‘90’s. By the aughts, Murray laments, the popularity of the Square began to diminish.

“There just weren’t as many people.” he shrugged, offering no explanation to the trend.

Turnbull, who has not played a tournament game since 1989 – his USCF is parked at 2390 – does not rule out the possibility of a return.

“I always thought I would go back [to playing in tournaments] after I retired. Just haven’t gotten to it yet,” he said.

But to the Square, to blitz?

“Nah,” the old master replied. “I get my fix from the bullet.”

The man who calls himself the Chess Mister declined to give his legal name. Given the added insistence that I not make any video recording for use with the magazine, I feel it is also fitting to exclude images here.

He is something of a corrosive wit, a feature evident in the way he has presented himself through the years. He admits his current moniker and signage are jabs at the great Mr. Turnbull, and in fact his original alias was also a piece of pointed allusion. Referring to a woman who called herself the Chess Lady sometime around the year 2000, he termed himself the Bearded Chess Lady, and with that title began his career in the Square.

Before that point, the Mister had not thought about chess, he contends, in decades, since dabbling in tournaments while a graduate student at U.C. Berkeley in the 1970’s. The jump to offering games for money was quick, though.

“The allure of making $100 in a day just playing out here, that was attractive to me,” he offered, matter-of-factly, a sigh in his breath lamenting that that was not to be a regular occurrence.

He started, after all, early in the millennium, when the Chess Master had noted the first major decline in attendance. Though he didn’t notice that so much, he did seem to feel another downturn some years later:

“When the recession hit in 2008, I think people were a little less eager to go throwing money to strangers here,” he theorized. “There were fewer tourists, and all that. But the thing is, it never really recovered here.”

An occasional FICS player, he cites the online game as one of the lasting factors in the decline of attendance in the Square. But he also notes that there are just generally so many more options for entertainment in the digital age, that patience for the game of chess is harder to expect. So why does he still come?

“Habit,” he shrugs, flashing a rare smile.

New Designs

As the infamous New England winter sets in, things always tend to quiet down in the Square. But it is when there are fewer faces that the lack of familiar ones is most felt.

The Mister still comes around a few times a week, putting his hours in, reading the paper as he waits for the rare customer. Andrey has not been seen in some months, though he is in good health. Simply taking a break, he says, though he sounds ambivalent on when he might return.

Esserman, normally one of the loudest and most visible of the Square’s players, is spending time abroad. Vadim and Ilya are busy with their classes. Some of the older masters simply aren’t up to coming down for blitz as often.

Among the players who do continue to frequent the café and the familiar outdoor tables, by and large a group of old friends of varying class player strength, conversation turns often to the rumors of renovation.

As part of a large scale renovation project on the Holyoke Center and the plaza, Harvard University proposed early in 2015 a redesigned square with some of the tables removed, where the familiar outdoor area would be encased in a glass structure. Designs proposed do feature some new chess tables added in.

The plan has met with some resistance, locals arguing the importance of the open space, while the company line has been that open access will ensure nothing to conflict with the outdoor culture that has built up.

At the time of this writing, after a number of public meetings, the city waits for the university to present an updated version of their plan, to assuage concerns before moving forward with a timetable. But the general sentiment in the Square is that mostly minor details are in question, and that change will be coming sooner or later.

All these designs do not threaten the end of chess in the city, nor the end of chess in the Square. But it would certainly not be the same.

I wanted to put this article together because, whatever may come next, the Square will change, and it is worth remembering just how special it has been.

There’s something to be said, in a town where every point of interest seems to be a square of sorts, for a place that becomes, simply, the Square.

All photos courtesy Tony Cortizas unless otherwise noted. |