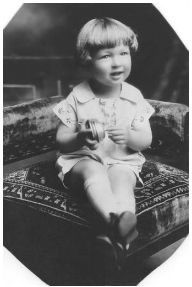

Harold Dondis was born at a very young age. Harold Dondis was born at a very young age.

Difficult as it may be to conceive for someone who had only encountered the man in his final epoch, Mr. Dondis’ frailness belied the strength of being and character that carried him through nearly a century, through societal troubles and through his personal tribulations, which included the untimely losses of a wife and a niece. Here was a sharp mind, a graduate of Harvard Law School who had risen through the ranks at Rich May to become full partner and to argue before the United States Supreme Court. And here was a man with a truly unique passion for the game of chess, discovered through poetry and founded upon a fascination with how the brain worked and how it could be improved.

-------

What most struck me about Harold, whom I first met around 2011, was just how universally beloved he seemed to be within the local chess community. Curmudgeons and malcontents, who seemed to gripe about everyone, spoke about the man with uncharacteristic reverence and admiration. One such player told the story of his first victory as a youngster over Harold, after which Mr. Dondis took him out for a celebratory ice cream.

Even in the contentious world of chess politics, he was a man who had seemingly made no enemies. It was Harold’s nature – the man did not want to mire himself in petty arguments, and had far more interest in understanding and implementing the logistics of positive change than in proving himself right.

Harold preceded me as MACA (then MSCA) president by some fifty years. His achievements in chess organization included playing a vital role in the 1966 founding and subsequent maintenance of the U.S. Chess Trust – a charitable organization which funded a number of major tournaments – and the 1980 certification of MACA as a 501(c)3 non-profit organization, which followed a decade-long effort to do so. All throughout, Mr. Dondis displayed a relentless pursuit of solving these organizations’ challenges, and a strident dedication to seeing his solutions through. This was simply Harold’s nature.

-------

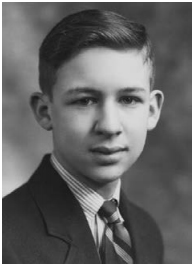

Harold Bayer Dondis was born in 1922 in Rockland, Maine, a harbor town of some seven thousand people at the time. He was the younger of two children of Ida (née Povich – yes, that Povich, second cousins some generations removed with the famed Maury) and Joseph Dondis, who ran a  movie theater in the town. The cinema sparked wonder in the young Harold, who claimed in a 2004 Chess Horizons interview to have seen every film played there during his childhood. He even worked as an usher for some time, but stopped so that his father could hire others, who were in more pressing need of work during the Depression. His parents had high hopes for Harold, who was a strong student. So when he had finished his schooling, they used what resources they had to send him off to Bowdoin College, Maine’s finest. Again, Harold excelled, and by 1942 he was off to Harvard Law School, from which he graduated three years later. movie theater in the town. The cinema sparked wonder in the young Harold, who claimed in a 2004 Chess Horizons interview to have seen every film played there during his childhood. He even worked as an usher for some time, but stopped so that his father could hire others, who were in more pressing need of work during the Depression. His parents had high hopes for Harold, who was a strong student. So when he had finished his schooling, they used what resources they had to send him off to Bowdoin College, Maine’s finest. Again, Harold excelled, and by 1942 he was off to Harvard Law School, from which he graduated three years later.

Turning his eyes toward practice in Boston, Harold found work at Burns, Blake and Rich (now Rich May Law), a corporate law firm founded eight years prior, and the only firm willing to hire Dondis, who was Jewish. Their newest employee would repay them with a fierce loyalty, sticking with the firm, where he eventually became a full partner, for more than seventy years.

-------

Harold Dondis learned the game of chess at the age of ten, after a counselor at his boys’ camp had grown tired of being beaten by the boy in checkers. He took a liking to the game instantly, and sometime later found a friend in town who shared his enjoyment. The two would play in a Rockland library on an almost daily basis, but never partook in any tournaments. In those days, and especially in Rockland, they were hard to find.

His chess adventures would not resume until the early 1960’s, when a date suggested they attend a poetry club in Dorchester. There, Harold met Jim Burgess, Boston Globe chess writer at the time. The two became friends, and Burgess introduced Dondis to Harry Lyman and others. Soon, Harold started participating in tournaments himself.

By the time of his win over then-U.S. Champion Bobby Fischer in a simultaneous exhibition less than five years later, he had become not only a player of around expert strength, but a vital part of the community and the president of the Massachusetts State Chess Association (now MACA).

His intimate knowledge of the local chess community was in fact vital in that win over Fischer, as Harold’s close friend Harry Lyman had won two prominent games as black against Dedham’s own Weaver Adams in what has become known as the Frankenstein-Dracula variation of the Vienna. As luck would have it, on the evening of March 2nd, 1964 in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Fischer found himself against Dondis, one of his fifty-six challengers that night, in the very line. Here, without further comment, is the crown jewel of Harold Dondis’ chess-playing journey:

GM Robert J. Fischer

Harold Dondis

Simultaneous Exhibition, Fitchburg

03.02.1964

Vienna Game [C27]

1. e4 e5 2. Nc3 Nf6 3. Bc4 Nxe4 4. Qh5 Nd6 5. Bb3 Nc6 6. d4 Nxd4 7. Nd5 Ne6 8. Qxe5 c6 9. Nc3 Qf6 10. Qxf6 gxf6

11. Nge2 Nf5 12. g4 Nfd4 13. Nxd4 Nxd4 14. Be3 Nxb3 15. axb3 d5 16. Rxa7 Rxa7 17. Bxa7 Bxg4 18. Bd4 Be7 19. Kd2 c5

0 – 1

The game is covered in depth in John Donaldson’s A Legend on the Road (Russell, 1994), about Fischer’s 1964 simul tour. It also features the following quote from Dondis:

“Fitchburg, site of the simul, is a mill town which, perhaps due to organizers like George Mirijanian, was quite wild about chess. As I recall, Fischer had asked for as many boards as possible. There was not enough room for the overflow crowd and it was so enthusiastic about seeing a possible world champion that, when Fischer erred against me, and a move later graciously resigned, the crowd bore me out of the room on its shoulders! I’ve never seen that in chess.”

-------

July 24th, 1964. In the wake of his passing, the fate of the Boston Globe chess column was in question, as no capable and willing candidate to replace Burgess was in sight. And so his friend Harold took it upon himself to take the reins, though he needed to get permission first – his firm represented the Boston Record, the Globe’s competition at the time.

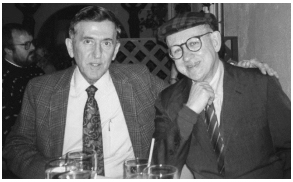

Sometime into his running the column, Harold found help from his friend John Curdo, he of the record tournaments won and the countless state championships. Curdo would provide annotations until his retirement from that post in 1998.

After Curdo’s departure, Harold enlisted the help of former U.S. Champion Patrick Wolff, who expanded the array of published games to feature a more international flavor. Wolff was a Belmont native, whom Dondis had previously known when the former was a precocious child storming up the ranks of competitive chess.

In more recent years, Wolff left the post as well, and FM Chris Chase, a close friend of Harold, took over as annotator. The column faced several cancellation scares, one in 2001 when ownership of the Boston Globe was transitioning and the other in early 2015. In both cases, the column returned, buoyed by an outcry among its loyal local readers. It is continued now under the sole stewardship of Chase, after more than fifty years with Dondis at the helm.

Perhaps Dondis’ most exciting work as chess writer came at the peak of the game’s interest in the United States, when in 1972 his old nemesis Bobby Fischer was in Reykjavik playing for the World Championship. For that event, Harold journeyed to Iceland, where he worked with Life Magazine Brad Darrach and Fischer’s manager Fred Cramer to get updates on the match relayed to the States. At one point, Cramer even called upon Harold to act as a legal counsel to resolve issues in the contentious and controversial match.

When Fischer threatened to withdraw from the match, it was Harold who came up with the idea of petitioning the Grandmaster with telegrams urging he resume. With the help of MACA’s Stephen Dann stateside, such a campaign was begun. Whether or not Fischer would have resumed if not for the campaign is unknowable, but there is the possibility that, in a remarkable career, this was Harold Dondis’ most profound impact on the world of chess.

-------

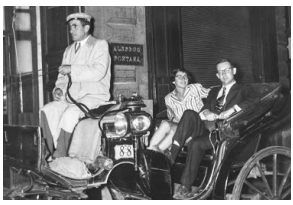

The longtime bachelor Harold finally settled down in the 1960’s. His wife was the remarkable Dr. Donis A. Dondis (1925 – 1984), who would eventually become dean of the Boston University School of Communication. Sadly, she passed at the age of 59 after a battle with cancer. Harold would remarry a few years later, and remained with his second wife, Claire, until his passing.

Harold Dondis’ legal career reached its grandest stage in 1976, when he argued on behalf of his client, Freetown, Massachusetts – based Algonquin SNG in the Supreme Court case Federal Energy Administration et al. v. Algonquin SNG, Inc, et al. The case pertained to an oil tariff in place at the time, and a number of Northeastern utility companies’ assertion of its unconstitutionality. Though Mr. Dondis would lose the case, the tariff was soon overturned.

Long fascinated with the nature of problem solving and how the human mind approaches it, Harold wrote three books on the subject, though none were published. In the last of these, Mental Improvement, he embarks on finding universally applicable truths of the nature of the human mind, and of building upon them a method for the titular goal. From the back cover:

“Human beings are given the joyful gift of life and functionality. It is a flame that rises brilliantly, though it must ultimately expire. To make the most of it is a sacred opportunity.”

-------

Harold Dondis passed away on December 10th, 2015, at the age of 93, when he suffered a heart attack during the second-round game of the Boylston Chess Club’s Thursday Night Swiss tournament. It was a hero’s end – the one Harold wanted – but it was difficult for the players that night to find comfort in its poetry. It was, after all, the sudden loss of a dear individual, a pillar of the chess community who had done so much and who meant so much to those players, some of whom had known Harold for forty years or more.

It also wasn’t Harold’s first heart attack at the board, and he alluded to that in his 2004 Chess Horizons interview:

“I’m not an impressive player, but I love [chess]. I’m 81. I still play it. I love it. I even had a heart attack during one game. It doesn’t bother me. I love it so much.”

Such was the man’s passion for the game of chess, and such was his passion for life. Fiercely loyal, dedicated to his friends and his community, he was a talented professional who took the time to use his legal acumen and writing ability to add so much to the world of chess in Massachusetts and in the United States.

Harold Dondis passed away at a very old age, but he will be sorely missed.

Special thanks to Christopher Chase, George Mirijanian, and Stephen Dann for their previous articles on Mr. Dondis and their help on this one.

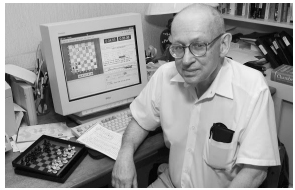

Photos, in order of appearance: a very young Harold Dondis; as a youth; with Curdo; with Wolff; with Chase; on his honeymoon with Donis in Paris; at home in his “Chess Center”

Photos courtesy Tony Cortizas and Claire Dondis |